In an ideal world, you might imagine that scientific papers were only cited by academics on the basis of their content. This might be true. But lots of other stuff can have an influence.

One classic paper from 1991, for example, found that academic papers covered by the New York Times received more subsequent citations. Now, you might reasonably suggest a simple explanation: the journalists of the Times were good at spotting the most important work. But the researchers looking into this were lucky. They noticed the opportunity for a natural experiment when the printers – but not the journalists – of the Times went on strike.

The editorial staff continued to produce a "paper of record", which was laid down in the archives, but never printed, never distributed and never read. The scientific articles covered in these unprinted newspapers didn't see a subsequent uplift in citations. That is, if we can take a moment, a very clever piece of opportunistic research.

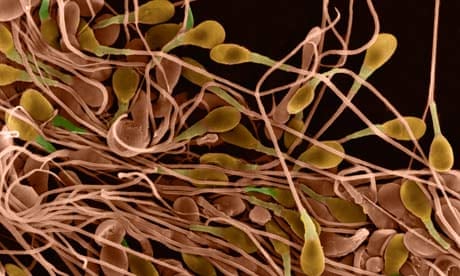

Meanwhile, a paper from the latest issue of Scientometrics shows that academic papers' titles might also be important. They took one year's worth of articles from six journals – 2,172 in total – and categorised their titles into three types: interrogative titles give the subject as a question, perhaps to arouse curiosity ("how long is a giant sperm?" is a favourite of that genre); descriptive titles give the method but not the answer ("a gene linkage study of Z"); declarative titles give the main conclusion ("X is associated with Y").

If you're feeling cute, these title styles reflect the three stages of science: the question, method and result. The descriptive titles are the most common, as you'd hope, because methods are the most important thing in science. But earlier research has shown that question marks in titles are becoming more common. That was done on a corpus of 20m papers, which is testament to the almost magical ability of computers to find patterns, in what looks like noise. (The paper wasn't called "Are Question-mark Titles Becoming More Common?")

Other previous work on 9,031 papers in 22 journals found that studies with longer titles had more citations: perhaps they're read more, as it's easier to see that they suit your interests. And papers with titles rated as "highly amusing", when presented in a list, get fewer citations. You might wonder if that's because funny titles are more likely to be scientific comment pieces, rather than citation-classics of original research, but the finding stood up when this factor was controlled for.

If you're interested, average title length and the prevalence of colons have both increased over time – this gets relevant in a moment – and papers with more authors have longer titles (perhaps reflecting squabbles, or a desire for clarity; basically this field is wide open for fun post-hoc hypotheses).

Meanwhile, this new paper in Scientometrics had two main findings. Articles with question marks in the titles tended to be downloaded more, but cited less; and article titles containing a colon had fewer downloads, and fewer citations.

As ever in science, you can't argue with the fact of these results, but you can argue over why they came out that way. Maybe question-mark titles are more ambiguous and playful, so you have to download them to see if they're relevant to your work, explaining the mismatch between downloads and citations?

That said, the only previous work on this specific question found that longer titles, colons and the presence of an acronym in the title were associated with more citations. Since this conflicts with the colon finding in our new study, you're left with a messy contradiction. The papers compared different journals, and the older one compared the top 25 most cited articles against the 25 least cited ones from each journal, rather than chasing the entire corpus. But I can't think why either of those factors could explain the disparity.

And since I'm not a story-spinner, there's no gloss here: I'm going to leave you with that inconsistency. The real world of evidence is often very irritating.